by Larry Caillouet

After three weeks at home we returned to Escapade in Providenciales, Turks and Caicos. We spent a day reprovisioning and doing the inevitable—installing equipment. We brought a new microwave oven with us, along with a new toilet pump for the aft head, a door latch for the forward head, and a fan to replace the one that died in the galley when it got soaked with a splash of seawater en route to Cartagena. We also brought two new crew—Richard, who had sailed with us on Escapade’s maiden voyage in the 2016 Bermuda Race, and Todd, who was new to the crew. We refueled and were ready to depart.

After three weeks at home we returned to Escapade in Providenciales, Turks and Caicos. We spent a day reprovisioning and doing the inevitable—installing equipment. We brought a new microwave oven with us, along with a new toilet pump for the aft head, a door latch for the forward head, and a fan to replace the one that died in the galley when it got soaked with a splash of seawater en route to Cartagena. We also brought two new crew—Richard, who had sailed with us on Escapade’s maiden voyage in the 2016 Bermuda Race, and Todd, who was new to the crew. We refueled and were ready to depart.

We left Providenciales the same way that we arrived—at high tide being led through tricky shoals by a pilot boat. High tide came at high noon, which was perfect for our first project. As soon as we cleared the slalom course exit from Provo, we dropped anchor in 20 feet of water. Just as we had anticipated, the hull had collected a small garden of sea life. Richard, Todd, and I were happy to jump into the warm and remarkably clear water to clean the hull. I had bought drywall taping knives and a painter’s multi-tool. Since I had scuba gear, I concentrated on the keel, propeller, shaft, and rudder while Richard and Todd worked on the hull and the bow thruster tube. It was fun to watch the scum, barnacles, and unidentified yucky stuff flying off the hull as we scraped. In fact, I think it was one of the most enjoyable dives I’ve ever had. A good time was had by all.

We left Providenciales the same way that we arrived—at high tide being led through tricky shoals by a pilot boat. High tide came at high noon, which was perfect for our first project. As soon as we cleared the slalom course exit from Provo, we dropped anchor in 20 feet of water. Just as we had anticipated, the hull had collected a small garden of sea life. Richard, Todd, and I were happy to jump into the warm and remarkably clear water to clean the hull. I had bought drywall taping knives and a painter’s multi-tool. Since I had scuba gear, I concentrated on the keel, propeller, shaft, and rudder while Richard and Todd worked on the hull and the bow thruster tube. It was fun to watch the scum, barnacles, and unidentified yucky stuff flying off the hull as we scraped. In fact, I think it was one of the most enjoyable dives I’ve ever had. A good time was had by all.

Since hurricane season had officially already started, we had some concern about the weather. It turned out that high wind was the opposite of the weather problem we faced. When we got underway there was barely a whisper of wind, so we motored away on a north-northwest course. We opened the mainsail to steady the motion of the boat and in hopes that it would add a half-knot or so to our speed, but it served mostly for decoration and to reaffirm our identity as sailors, not that other kind of boater. We motored all night, and all day, and all night, and all day. Norfolk is about 1000 miles from Turks and Caicos and Escapade has a calculated motoring range of 1000 miles on full fuel tanks, but we didn’t want to find out if that calculation was accurate. So we held the engine to a fuel efficient rpm and when the wind would occasionally make a contribution to our speed, we would reduce engine rpm accordingly.

Our doldrum days passed without incident. That gave us plenty of time to enjoy sunny days, starry nights, and round after round of storytelling. The storytelling well never ran dry and even when we made landfall the bucket was still full of untold stories. The sea became so flat and smooth it took on an appearance like oil and gave us the opportunity to see its true color, a gorgeous cobalt blue that was mesmerizing in its beauty.

Our doldrum days passed without incident. That gave us plenty of time to enjoy sunny days, starry nights, and round after round of storytelling. The storytelling well never ran dry and even when we made landfall the bucket was still full of untold stories. The sea became so flat and smooth it took on an appearance like oil and gave us the opportunity to see its true color, a gorgeous cobalt blue that was mesmerizing in its beauty.

After about 60 hours of motoring we finally found wind, or wind found us, and we added the genoa and the staysail to the main. The customary photos of the spinnaker flying gloriously will be missing from this report because we never had the right conditions to fly it. Too little wind, too much wind, or wind from the wrong direction denied any plan to use it, so we applied our sail trimming expertise to the other three sails—when we felt like it. Cruising is not racing and it’s easy to become complacent on long ocean passages. We discovered another incentive to not tinker with the trim of the sails too much. Any time we used the power winches to trim the genoa or the outhaul on the main, we lost our navigation instruments. Sometimes this included the autopilot and sometimes only the wind speed and wind angle readouts on the multifunction display. We had to reboot the instruments each time to get the readings back. We decided that this problem was related to the battery charging problems that we had been having ever since the new inverter/charger was installed in Dominican Republic. We also decided that there was nothing we could do about it out in the Atlantic, so we became very judicious in our use of the power winches. Still, with racing in our blood, we kept the boat moving pretty well.

One day when nothing special was happening, I spotted a couple of dolphins a hundred yards out to starboard. I told everyone to get their cameras ready because they would be visiting us soon, and they did. Dolphins seem to love playing with passing boats, like dogs chasing cars, and they don’t get a lot of opportunities out in the Atlantic where we were. There were 7 or 8 dolphins in the pod—it’s hard to count them when they are darting back and forth in front of the hull or zipping off on a larger loop and returning to join the fun. They entertained us for about 10-12 minutes and showed us that a sailboat is no match for their graceful and effortless speed.

One day when nothing special was happening, I spotted a couple of dolphins a hundred yards out to starboard. I told everyone to get their cameras ready because they would be visiting us soon, and they did. Dolphins seem to love playing with passing boats, like dogs chasing cars, and they don’t get a lot of opportunities out in the Atlantic where we were. There were 7 or 8 dolphins in the pod—it’s hard to count them when they are darting back and forth in front of the hull or zipping off on a larger loop and returning to join the fun. They entertained us for about 10-12 minutes and showed us that a sailboat is no match for their graceful and effortless speed.

Partway through the third day we picked up wind again, even though the weather report said we wouldn’t have any. It was great to turn the engine off and get back to doing what sailboats are meant to do. We discovered that without the engine running the house batteries were quickly depleted. This caused the electronic instruments to be even more finicky and the refrigeration suffered, so we ran the generator almost continuously when the engine wasn’t running. The generator uses less fuel than the engine, but still we kept an eye on the fuel gauge.

The next issue became the crossing of the Gulf Stream, which can be your friend or your worst enemy. Normally sailors plan to cross it at its narrowest point to minimize exposure to what can be very rough weather. If the wind is blowing south against the northward flowing Stream, it can be quite tempestuous. We were fortunate to have a favorable wind and were able to use the Stream like a moving sidewalk. On only 12 knots of wind we achieved the amazing speed of 10 knots, which is otherwise nearly impossible in Escapade. Because the wind, the current, and the boat were all moving in the same direction, it actually felt like we were sailing slowly and gently.

The next issue became the crossing of the Gulf Stream, which can be your friend or your worst enemy. Normally sailors plan to cross it at its narrowest point to minimize exposure to what can be very rough weather. If the wind is blowing south against the northward flowing Stream, it can be quite tempestuous. We were fortunate to have a favorable wind and were able to use the Stream like a moving sidewalk. On only 12 knots of wind we achieved the amazing speed of 10 knots, which is otherwise nearly impossible in Escapade. Because the wind, the current, and the boat were all moving in the same direction, it actually felt like we were sailing slowly and gently.

We reached Norfolk, Virginia, just inside the mouth of the Chesapeake late Friday afternoon and anchored outside Little Creek harbor to wait for Customs and Immigration to open in the morning. The storms that never materialized while we were sailing were waiting for us at Norfolk. Soon after we anchored we began to hear a roaring sound in the distance. It grew louder and louder and reminded us of tornado movies like Twister, but there were no funnel clouds, just lots of wind. Then the light show began. Broad flashes of lightning lit up the night and crackles of lightning etched jagged lines across the sky. We didn’t feel threatened but an old Christian hymn, “Will your anchor hold in the storms of life?” came to my mind. Yes, Escapade’s 99-pound Spade anchor held and we enjoyed the show.

We reached Norfolk, Virginia, just inside the mouth of the Chesapeake late Friday afternoon and anchored outside Little Creek harbor to wait for Customs and Immigration to open in the morning. The storms that never materialized while we were sailing were waiting for us at Norfolk. Soon after we anchored we began to hear a roaring sound in the distance. It grew louder and louder and reminded us of tornado movies like Twister, but there were no funnel clouds, just lots of wind. Then the light show began. Broad flashes of lightning lit up the night and crackles of lightning etched jagged lines across the sky. We didn’t feel threatened but an old Christian hymn, “Will your anchor hold in the storms of life?” came to my mind. Yes, Escapade’s 99-pound Spade anchor held and we enjoyed the show.

In the morning we docked at Little Creek Marina and called Customs and Border Protection to check in. Two CBP agents and one Agriculture agent came to our boat and in the old-fashioned face-to-face method easily cleared us in without any SVRS, ROAM, or other electronic acronyms. We ate dinner at the nearby Cutty Sark Restaurant and Bar which can best be described as “authentic.” The live music was mostly 70’s and 80’s songs, which triggered a “name that tune and singer” contest at our table.

When we left Norfolk to sail up the Chesapeake to Annapolis, we discovered a new problem—the autopilot refused to work, another issue caused by the bank of house batteries failing. That doesn’t sound like much of a problem unless you’ve tried to steer a course without any fixed visual reference points. The lower Chesapeake is so wide that you think that you are still on the ocean. There is no land to be seen ahead of you or on either side of you. There is a compass, of course, but steering a boat while watching the constantly moving dial of a compass is exceedingly tedious. By day whoever was helming tried to find a cloud that wasn’t moving too fast and steered toward it. By night we could have used the stars but heavy cloud cover eliminated that possibility. So we used lighted channel markers and referred frequently to the route I had plotted on the chart plotter before we set sail.

When we left Norfolk to sail up the Chesapeake to Annapolis, we discovered a new problem—the autopilot refused to work, another issue caused by the bank of house batteries failing. That doesn’t sound like much of a problem unless you’ve tried to steer a course without any fixed visual reference points. The lower Chesapeake is so wide that you think that you are still on the ocean. There is no land to be seen ahead of you or on either side of you. There is a compass, of course, but steering a boat while watching the constantly moving dial of a compass is exceedingly tedious. By day whoever was helming tried to find a cloud that wasn’t moving too fast and steered toward it. By night we could have used the stars but heavy cloud cover eliminated that possibility. So we used lighted channel markers and referred frequently to the route I had plotted on the chart plotter before we set sail.  After 24 hours of motorsailing we found ourselves in familiar territory, waiting for the draw bridge to open on Spa Creek in Annapolis, which we have always considered Escapade’s home port. It felt good to be back and a variety of water fowl welcomed us home.

After 24 hours of motorsailing we found ourselves in familiar territory, waiting for the draw bridge to open on Spa Creek in Annapolis, which we have always considered Escapade’s home port. It felt good to be back and a variety of water fowl welcomed us home.

We were working on cleaning the boat and packing when we started getting messages asking if we were okay. Yes, of course we were—why wouldn’t we be? We learned that a terrible shooting had just occurred in Annapolis at the Capital Gazette newspaper office, about 2 miles away from us. It was another senseless murder rampage stemming from the growing inability of Americans to manage their anger, respect life, and behave civilly.

The following day we celebrated the completion of our 2018 Gringo Escapade in our traditional way by going to Chick and Ruth’s Deli on Main Street to eat crab cakes and chocolate peanut butter pie. We were still strolling by the waterfront and seeking relief from the heat when a few thousand people marched by in a solemn vigil remembering those who died and protesting the needless violence in Annapolis and in the USA. Although we fully agreed with their sentiments, we didn’t join the vigil. Somehow I felt that I would be an intruder, although that feeling doesn’t quite make sense to me now.

The following day we celebrated the completion of our 2018 Gringo Escapade in our traditional way by going to Chick and Ruth’s Deli on Main Street to eat crab cakes and chocolate peanut butter pie. We were still strolling by the waterfront and seeking relief from the heat when a few thousand people marched by in a solemn vigil remembering those who died and protesting the needless violence in Annapolis and in the USA. Although we fully agreed with their sentiments, we didn’t join the vigil. Somehow I felt that I would be an intruder, although that feeling doesn’t quite make sense to me now.

As I am writing this final chapter of the Gringo Escapades, it is Independence Day in the United States. I’m grateful to be a citizen of this great country, even with all its obvious and serious defects. The USA began as a great escapade, an adventure fraught with risk and promise. May that escapade remember its roots as the adventure continues. And may it find a true North Star to guide it through rough, confusing, and uncertain waters.

As I am writing this final chapter of the Gringo Escapades, it is Independence Day in the United States. I’m grateful to be a citizen of this great country, even with all its obvious and serious defects. The USA began as a great escapade, an adventure fraught with risk and promise. May that escapade remember its roots as the adventure continues. And may it find a true North Star to guide it through rough, confusing, and uncertain waters.

The Yankee Doodle will be held Sunday July 1st. The skippers meeting will be at 11:00 AM with racing shortly thereafter. Let’s all raise a glass in memory of our mate Herb Siewert as this was probably his favorite race of the year. Fair winds Herb !

The Yankee Doodle will be held Sunday July 1st. The skippers meeting will be at 11:00 AM with racing shortly thereafter. Let’s all raise a glass in memory of our mate Herb Siewert as this was probably his favorite race of the year. Fair winds Herb !

The Glow Regatta is Saturday June 23rd, this is our Night Regatta – Brats and Dogs around 6pm. Skippers meeting to follow. Bring a side (BUENOS NO CHIPS!). Make sure your lights work or have a way to make a light.

The Glow Regatta is Saturday June 23rd, this is our Night Regatta – Brats and Dogs around 6pm. Skippers meeting to follow. Bring a side (BUENOS NO CHIPS!). Make sure your lights work or have a way to make a light.

We left Cartagena as night fell and knew we would have to motor for several hours because the sea was in the wind shadow of Colombia. When we finally got into clear air we had the winds that usually are found in the Caribbean—15-20 knots from the east. We hoisted the sails (actually we unfurled them) and soon hit our stride at 8+ knots. When we sailed south to Colombia we had the benefit of waves on our quarter pushing us along. Now we had waves on our bow splashing over the boat and forcing us to close ports and hatches. Sometimes we zipped down the cockpit enclosure panels on the weather side of the boat to keep the cockpit and its inhabitants dry. But no one was complaining about 8+ knots.

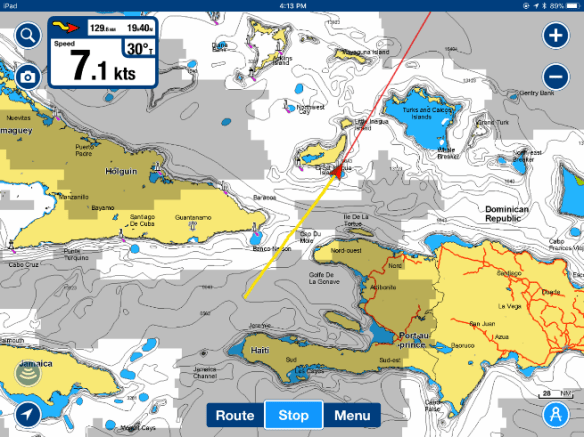

We left Cartagena as night fell and knew we would have to motor for several hours because the sea was in the wind shadow of Colombia. When we finally got into clear air we had the winds that usually are found in the Caribbean—15-20 knots from the east. We hoisted the sails (actually we unfurled them) and soon hit our stride at 8+ knots. When we sailed south to Colombia we had the benefit of waves on our quarter pushing us along. Now we had waves on our bow splashing over the boat and forcing us to close ports and hatches. Sometimes we zipped down the cockpit enclosure panels on the weather side of the boat to keep the cockpit and its inhabitants dry. But no one was complaining about 8+ knots. When we zoomed in to the HaiCuJa Triangle on the chartplotter to set a waypoint, we discovered a small island of only 2 square miles sitting between Haiti and Jamaica. It is named Navassa Island and has been administered by the USA since 1857. It piqued our curiosity to find a US territory that we had never heard of in this out-of-the-way location, so we decided to use it as our first waypoint. If we arrived in daylight perhaps we could anchor there and have lunch. We did arrive exactly at lunch time, but this island had no place to anchor. It was long and flat with steep cliffs coming straight down to the water. It was covered with small green foliage, but the only sign that any human had ever set foot on it was a smooth path that led down to the rocky cliff at one point. So we saluted it and sailed on.

When we zoomed in to the HaiCuJa Triangle on the chartplotter to set a waypoint, we discovered a small island of only 2 square miles sitting between Haiti and Jamaica. It is named Navassa Island and has been administered by the USA since 1857. It piqued our curiosity to find a US territory that we had never heard of in this out-of-the-way location, so we decided to use it as our first waypoint. If we arrived in daylight perhaps we could anchor there and have lunch. We did arrive exactly at lunch time, but this island had no place to anchor. It was long and flat with steep cliffs coming straight down to the water. It was covered with small green foliage, but the only sign that any human had ever set foot on it was a smooth path that led down to the rocky cliff at one point. So we saluted it and sailed on. We were surprised to find that we still had very good wind after entering the HaiCuJa triangle. The forecast had been for no wind at all in this mini-gulf, but we were still hitting 8+ and sometime topped 9 knots. Then it happened: God turned the wind off. It didn’t die gradually—it just suddenly quit. So we started the motor and set a course through the gap between Cuba and Haiti toward Grand Inagua Island, the southernmost island of the Bahamas.

We were surprised to find that we still had very good wind after entering the HaiCuJa triangle. The forecast had been for no wind at all in this mini-gulf, but we were still hitting 8+ and sometime topped 9 knots. Then it happened: God turned the wind off. It didn’t die gradually—it just suddenly quit. So we started the motor and set a course through the gap between Cuba and Haiti toward Grand Inagua Island, the southernmost island of the Bahamas. I was on watch when a playful pod of dolphins began doing their circus tricks alongside the boat. Sometimes they did synchronized leaps from the water. At other times they happily raced the boat, riding the bow wave and crisscrossing back and forth under the boat. It was easy to see that they were holding back to stay with us. At our top speed the dolphins were just out for a stroll and some fun and games.

I was on watch when a playful pod of dolphins began doing their circus tricks alongside the boat. Sometimes they did synchronized leaps from the water. At other times they happily raced the boat, riding the bow wave and crisscrossing back and forth under the boat. It was easy to see that they were holding back to stay with us. At our top speed the dolphins were just out for a stroll and some fun and games. The first order of business after Customs and Immigration on the next morning was to get a marine mechanic to the boat to deal with some problems that had plagued us. Provo Diving was in the slip next to Escapade, so Greg and Elaine went diving while Diana and I met with Giles from Caribbean Diesel and Marine. It was reassuring to deal with a knowledgeable mechanic in English again. Giles discovered that the settings on the charger/inverter were set for lead acid batteries, not the AGM batteries that Escapade uses.

The first order of business after Customs and Immigration on the next morning was to get a marine mechanic to the boat to deal with some problems that had plagued us. Provo Diving was in the slip next to Escapade, so Greg and Elaine went diving while Diana and I met with Giles from Caribbean Diesel and Marine. It was reassuring to deal with a knowledgeable mechanic in English again. Giles discovered that the settings on the charger/inverter were set for lead acid batteries, not the AGM batteries that Escapade uses.  A few adjustments solved the electrical problem that began in Dominican Republic and was not solved in Cartagena. Giles used a trick I didn’t know to burp a giant air bubble from the starboard sea water intake. That solved the problem of inadequate water intake for the air conditioning and the water maker. Soon the problems were all dealt with and we were free to move about the island. Greg and Elaine rented a car and we set off to see the island. The land itself is mostly dusty sun bleached coral chalk—not particularly appealing to those of us who love the rich green foliage of Kentucky and the Windward Islands of the Caribbean. But the waters around TCI are indescribably beautiful. My cameras were simply inadequate to capture the nuanced shades of blue, blue-green, aqua, seafoam green, and turquoise that surrounded the islands and filled the bays. Our first excursion was along the south shore of Chalk Sound. Beautiful houses enjoyed fabulous views of the sea to the south and the sound to the north. Within Chalk Sound were many small islets that would make exploring it by water intriguing. And at the end of the road was a property called Emerald Bay. In addition to two impressive homes, it had a turntable for crossing the moat they created by cutting through the rock to let the sea in. It’s for rent if you’ve got the big bucks.

A few adjustments solved the electrical problem that began in Dominican Republic and was not solved in Cartagena. Giles used a trick I didn’t know to burp a giant air bubble from the starboard sea water intake. That solved the problem of inadequate water intake for the air conditioning and the water maker. Soon the problems were all dealt with and we were free to move about the island. Greg and Elaine rented a car and we set off to see the island. The land itself is mostly dusty sun bleached coral chalk—not particularly appealing to those of us who love the rich green foliage of Kentucky and the Windward Islands of the Caribbean. But the waters around TCI are indescribably beautiful. My cameras were simply inadequate to capture the nuanced shades of blue, blue-green, aqua, seafoam green, and turquoise that surrounded the islands and filled the bays. Our first excursion was along the south shore of Chalk Sound. Beautiful houses enjoyed fabulous views of the sea to the south and the sound to the north. Within Chalk Sound were many small islets that would make exploring it by water intriguing. And at the end of the road was a property called Emerald Bay. In addition to two impressive homes, it had a turntable for crossing the moat they created by cutting through the rock to let the sea in. It’s for rent if you’ve got the big bucks. The next day we drove across a small bridge to Middle Caicos, which is even less populous than North Caicos. We had lunch at Mudjin Bar & Grill which sits on a hill above caves that go down to the beach at Dragon Cay. At Bambarra Beach we waded in knee deep sea water a half mile out to Pelican Cay and back. If Mayberry could have a suburb, it would be Middle Caicos.

The next day we drove across a small bridge to Middle Caicos, which is even less populous than North Caicos. We had lunch at Mudjin Bar & Grill which sits on a hill above caves that go down to the beach at Dragon Cay. At Bambarra Beach we waded in knee deep sea water a half mile out to Pelican Cay and back. If Mayberry could have a suburb, it would be Middle Caicos.

Then with a curved needle I sewed the bitter end of the new halyard to the cut end of the old halyard. When this was done, Greg started pulling the old halyard down through the mast. I was absolutely elated when I saw the new halyard go over the turning block at the masthead and easily follow the old halyard down through the mast. I thought the job was over, but when the thimble end of the new halyard reached the top of the mast, my elation turned to frustration. I had led the halyard through a steel tool ring on the bosun’s chair to carry it up the mast with me and that ring was too small to allow the thimble end of the halyard to pass through. “We will have to pull the new halyard back out and do it over,” Greg said. “No way,” I said. “Put the angle grinder in a bag and send it up to me.” So I cut the steel ring off the bosun’s chair, attached the halyard to the top of the genoa furler, and the celebration began.

Then with a curved needle I sewed the bitter end of the new halyard to the cut end of the old halyard. When this was done, Greg started pulling the old halyard down through the mast. I was absolutely elated when I saw the new halyard go over the turning block at the masthead and easily follow the old halyard down through the mast. I thought the job was over, but when the thimble end of the new halyard reached the top of the mast, my elation turned to frustration. I had led the halyard through a steel tool ring on the bosun’s chair to carry it up the mast with me and that ring was too small to allow the thimble end of the halyard to pass through. “We will have to pull the new halyard back out and do it over,” Greg said. “No way,” I said. “Put the angle grinder in a bag and send it up to me.” So I cut the steel ring off the bosun’s chair, attached the halyard to the top of the genoa furler, and the celebration began.  When I pulled a cold one out of the refrigerator, their faces lit up. “These Gringos are slow,” they thought, “but they finally caught on.” Soon the beers were finished, the papers were finished, and we were ready to depart.

When I pulled a cold one out of the refrigerator, their faces lit up. “These Gringos are slow,” they thought, “but they finally caught on.” Soon the beers were finished, the papers were finished, and we were ready to depart.  We doubled our speed and doubled our pleasure. As a general rule, we don’t fly the spinnaker at night, but as a general rule we don’t have perfect conditions and a hundred miles to go, so we left it up through most of the night. Sometime before morning we turned on the deck lights and snuffed the spinnaker when we needed to change course for Beata.

We doubled our speed and doubled our pleasure. As a general rule, we don’t fly the spinnaker at night, but as a general rule we don’t have perfect conditions and a hundred miles to go, so we left it up through most of the night. Sometime before morning we turned on the deck lights and snuffed the spinnaker when we needed to change course for Beata.  At 8 pm we weighed anchor and put up the full cutter rig–mainsail, genoa, and staysail. In the lee of the island, winds were quite light, but when we got beyond it, winds picked up to 15-17 knots and

At 8 pm we weighed anchor and put up the full cutter rig–mainsail, genoa, and staysail. In the lee of the island, winds were quite light, but when we got beyond it, winds picked up to 15-17 knots and  Even with a slow start we reached the midpoint of the crossing to Cartagena in 37 hours. With no land to impede the winds, we maintained our speed the rest of the way and finished the Cartagena 500 in 66 hours, an average speed of 7.57 knots entirely on sail. It was exciting to see the ocean crossing potential of

Even with a slow start we reached the midpoint of the crossing to Cartagena in 37 hours. With no land to impede the winds, we maintained our speed the rest of the way and finished the Cartagena 500 in 66 hours, an average speed of 7.57 knots entirely on sail. It was exciting to see the ocean crossing potential of  We arrived at Cartagena in the early afternoon and decided to use the Boca Grande entrance to the harbor. Although Boca Grande means “big mouth,” this is an ironically narrow mouth. Cartagena was the most important Spanish port in Spain’s “God, Gold, and Glory” heyday, so to fend off their British rivals, pirates, and various other marauders the Spanish built a low stone wall across the mouth of the bay leaving only a small opening for boats to pass through. The wall was below the surface of the sea, so it would be easy for an uninformed vessel to shipwreck into the wall while the crew admired the fine bay. The opening is marked today with a red buoy on one side and a green one on the other side, so after questioning ashore whether the markers were accurate and reliable, we ventured through the Big Mouth into Bahia de Cartagena.

We arrived at Cartagena in the early afternoon and decided to use the Boca Grande entrance to the harbor. Although Boca Grande means “big mouth,” this is an ironically narrow mouth. Cartagena was the most important Spanish port in Spain’s “God, Gold, and Glory” heyday, so to fend off their British rivals, pirates, and various other marauders the Spanish built a low stone wall across the mouth of the bay leaving only a small opening for boats to pass through. The wall was below the surface of the sea, so it would be easy for an uninformed vessel to shipwreck into the wall while the crew admired the fine bay. The opening is marked today with a red buoy on one side and a green one on the other side, so after questioning ashore whether the markers were accurate and reliable, we ventured through the Big Mouth into Bahia de Cartagena.  Cartagena is built on a combination of islands and mainland bridged together around a bay. Our marina, Club de Pesca, was located inside the walled fort San Sebastian del Pastelillo on Manga island. This happened to be a stop on the route of the Hop-on Hop-off city sightseeing bus, so we bought a ticket and hopped on. It took 90 minutes to complete the tour of the city which gave us a great overview of places to return to. Much of Cartagena is new and modern with high rise apartments, condos, and office buildings dominating the skyline, but it is the historic Old Town that draws tourists to Cartagena. We were told that Gethsemane, a neighborhood inside the walled city, was once the most dangerous neighborhood in Cartagena when the drug wars were raging, but now is considered a chic and desirable location. Bars like the Havana Tavern are famous for their night life.

Cartagena is built on a combination of islands and mainland bridged together around a bay. Our marina, Club de Pesca, was located inside the walled fort San Sebastian del Pastelillo on Manga island. This happened to be a stop on the route of the Hop-on Hop-off city sightseeing bus, so we bought a ticket and hopped on. It took 90 minutes to complete the tour of the city which gave us a great overview of places to return to. Much of Cartagena is new and modern with high rise apartments, condos, and office buildings dominating the skyline, but it is the historic Old Town that draws tourists to Cartagena. We were told that Gethsemane, a neighborhood inside the walled city, was once the most dangerous neighborhood in Cartagena when the drug wars were raging, but now is considered a chic and desirable location. Bars like the Havana Tavern are famous for their night life. We began with a tour of the Cathedral of San Pedro Claver. This 16

We began with a tour of the Cathedral of San Pedro Claver. This 16 After the tour of the church we walked through the Plaza de Simon Bolivar where vendors were selling the usual tourist items and specialties such as maracas and boxes of cigars which claimed to be Cuban, but the most interesting vendors were the women wearing colorful traditional dresses. They were carrying large bowls of fruit on their heads and were not selling the fruit but selling the right to take their photos.

After the tour of the church we walked through the Plaza de Simon Bolivar where vendors were selling the usual tourist items and specialties such as maracas and boxes of cigars which claimed to be Cuban, but the most interesting vendors were the women wearing colorful traditional dresses. They were carrying large bowls of fruit on their heads and were not selling the fruit but selling the right to take their photos. Metal sculptures of children playing were located throughout the plaza.

Metal sculptures of children playing were located throughout the plaza.  Days were very hot in Cartagena, so we toured the Castillo de San Felipe de Barajas early the next morning. San Felipe is the largest fortress built in the Americas by the Spanish Empire.

Days were very hot in Cartagena, so we toured the Castillo de San Felipe de Barajas early the next morning. San Felipe is the largest fortress built in the Americas by the Spanish Empire.  It stands on a high hill overlooking the bay and the city below. Its large guns could pound enemy ships at sea and its high walls were a formidable barrier to land assaults. In addition to its sheer size and height, the fortress was built with several fall-back positions and a series of underground tunnels that were rigged with explosives that could be detonated as the enemy advanced. The audio tour was rather detailed and by the time we finished the tour, the day was getting hot, hot, hot. We went back to the boat to rest and cool off.

It stands on a high hill overlooking the bay and the city below. Its large guns could pound enemy ships at sea and its high walls were a formidable barrier to land assaults. In addition to its sheer size and height, the fortress was built with several fall-back positions and a series of underground tunnels that were rigged with explosives that could be detonated as the enemy advanced. The audio tour was rather detailed and by the time we finished the tour, the day was getting hot, hot, hot. We went back to the boat to rest and cool off.  By 4 pm the day had cooled, or maybe it was just us, so we took a taxi to the Torre Del Reloj, the Clock Tower that is the entrance to the walled Old Town. By the way, pirates are still active in Cartagena; they are called taxis now. We had a guided walking tour which was mostly in Spanish but with brief summaries in English.

By 4 pm the day had cooled, or maybe it was just us, so we took a taxi to the Torre Del Reloj, the Clock Tower that is the entrance to the walled Old Town. By the way, pirates are still active in Cartagena; they are called taxis now. We had a guided walking tour which was mostly in Spanish but with brief summaries in English.  It began with a tour of the Candy Street where shop after shop sold all sorts of specialty candies—nothing that you could buy in an American grocery store. We saw several important churches including the Cathedral that had been visited by Pope John Paul II and more recently by Pope Francis. We also saw the Palace of the Inquisition, but the tour wasn’t entirely spiritual. We toured the Gold Museum which had a lot of items made of gold—behind glass and well-guarded. We also toured the Emerald Museum which was informative but mainly a vehicle to sell Colombian emeralds. After the tour we found a gelato shop that we couldn’t resist.

It began with a tour of the Candy Street where shop after shop sold all sorts of specialty candies—nothing that you could buy in an American grocery store. We saw several important churches including the Cathedral that had been visited by Pope John Paul II and more recently by Pope Francis. We also saw the Palace of the Inquisition, but the tour wasn’t entirely spiritual. We toured the Gold Museum which had a lot of items made of gold—behind glass and well-guarded. We also toured the Emerald Museum which was informative but mainly a vehicle to sell Colombian emeralds. After the tour we found a gelato shop that we couldn’t resist.  We ended this day’s touring with dinner at Cande’, a restaurant recommended to us as very authentically Colombian. It was upscale with great food and fine presentation, but the most memorable part of the evening was two dancers who came out into the restaurant three times in different costumes and performed classic Colombian dances. In one of the dances the woman came to various men who were dining in the restaurant and with a sultry look on her face put a fake sword down inside the front of the men’s shirts. Somehow I escaped getting my heart cut out.

We ended this day’s touring with dinner at Cande’, a restaurant recommended to us as very authentically Colombian. It was upscale with great food and fine presentation, but the most memorable part of the evening was two dancers who came out into the restaurant three times in different costumes and performed classic Colombian dances. In one of the dances the woman came to various men who were dining in the restaurant and with a sultry look on her face put a fake sword down inside the front of the men’s shirts. Somehow I escaped getting my heart cut out.  We had dinner at a fun little diner called “Say Cheese.” The menu was dominated by cheese dishes including the absolutely best grilled cheese sandwich that I’ve ever tasted. What can you do with a grilled cheese sandwich? You have to go there to find out. The young people working behind the counter seemed to be having as much fun as those of us who were eating. When I raised my camera to them and said “Say Cheese,” they didn’t miss a beat.

We had dinner at a fun little diner called “Say Cheese.” The menu was dominated by cheese dishes including the absolutely best grilled cheese sandwich that I’ve ever tasted. What can you do with a grilled cheese sandwich? You have to go there to find out. The young people working behind the counter seemed to be having as much fun as those of us who were eating. When I raised my camera to them and said “Say Cheese,” they didn’t miss a beat.  Night was falling as we motored out of Bahia de Cartagena through the Big Mouth. We were treated to a lovely evening silhouette of this charming city. Adios, Cartagena!

Night was falling as we motored out of Bahia de Cartagena through the Big Mouth. We were treated to a lovely evening silhouette of this charming city. Adios, Cartagena!